A brief introduction to… Human-centred design

.@cityofkingston participated in @BloombergDotOrg @CPI_foundation Innovation Training to help cities adopt cutting-edge innovation techniques that engage residents in testing, adapting & scaling ideas w/ potentially long-term impact.

Share article"It was initially hard to settle in Kingston due to the lack of socio-cultural diversity in the community. However, getting a job positively impacted my experiences & inculcated a sense of belonging by allowing me to start developing a network." Lakshay Raheja

Share articleThe #COVID19 pandemic highlighted concerns around workforce development in @cityofkingston, now the city wants to fix this problem to ensure longer-term economic prosperity. Read this @CPI_foundation article on a more human approach to this issue.

Share articleWe put our vision for government into practice through learning partner projects that align with our values and help reimagine government so that it works for everyone.

From February 2020 to May 2021, the City of Kingston in Ontario, Canada participated in Bloomberg Philanthropies’ Innovation Training. Innovation Training, delivered in partnership with the Centre for Public Impact, is designed to help cities adopt cutting-edge innovation techniques that engage residents in testing, adapting, and scaling ideas with the potential for long-term impact. The City of Kingston was selected as one of 12 cities to participate in Innovation Training, with a focus on addressing workforce development challenges in the City. As training was about to begin, the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic, were just beginning to be felt. The pandemic fundamentally shifted the way the City’s team, comprised of eleven staff members from seven departments, worked together and understood adaptive, people-focused design.

The pandemic highlighted preexisting concerns around workforce development in Kingston. Even before COVID-19, labour shortages were a consistent and growing concern across Eastern Ontario. Many employers struggled to address a longer-term shortage of skilled workers while backfilling for a wave of anticipated retirements. The City of Kingston wanted to fix this problem to ensure longer-term economic prosperity.

It’s impossible to discuss workforce support and economic recovery without considering the Kingston community’s COVID-19 experience. The pandemic swept through the province of Ontario in early 2020, with the region’s first positive cases announced on March 17, 2020. The COVID-19 pandemic exposed fault lines that had always existed by causing more immediate employment shortages and job security challenges for residents, especially in sectors like accommodations, food services and the arts. Kingston experienced an 11.7 per cent loss of employment since the outset of the pandemic. Simultaneously, employers were faced with another obstacle in attracting and retaining skilled talent. While we understood this dynamic was the root of the problem, we had to decide when and where to intervene. Our guidance came from one key concept: fostering economic resilience. Getting people into the job market and keeping them there would set the groundwork for targeted talent attraction interventions.

Many of the jobless were individuals who may always have a number of barriers to employment, but were now directly out of work because of the pandemic. Thus, as we began to explore this problem, we settled on two initial considerations: “lower-income” and “at-risk.”

Immediately, we had concerns with these considerations: while lower-income and at-risk individuals typically experience disproportionate job insecurity, the terms “lower-income” and “at-risk” are too broad to help identify one major policy intervention. Moreover, assuming there would be “one fix” is a characteristic assumption of overly ambitious and ultimately poor program design. This lesson was exposed through a structured research program consisting of in-person interviews with at-risk community members and community advocates.

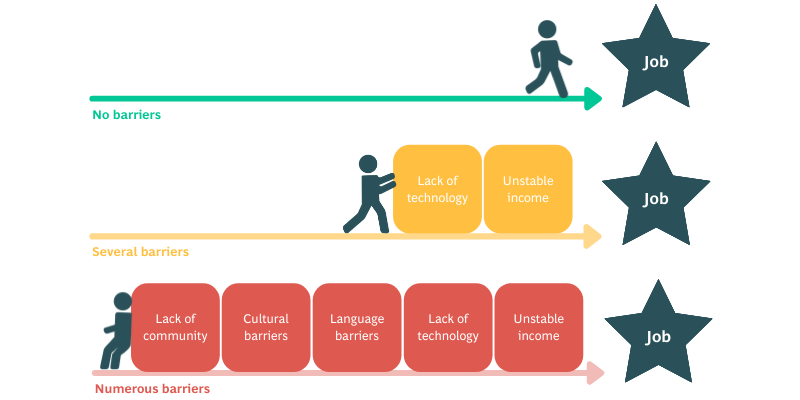

We learned two things:

The “lower-income” or “at risk” experience was composed of numerous separate, compounding factors. Each factor, including included language, cultural background, financial security, in-person support networks, and technical competency, could make it incrementally more difficult to secure stable employment.

These individuals often had problems connecting, particularly during the pandemic. Physical distancing forced people to rely on technology and this technology was not universally available to the people who needed it.

As a result, the first major realignment of our hypothesis was to focus on the factors, not the outcome. By intercepting negative factors with high-impact interventions, we could address some of the root causes behind job insecurity in Kingston.

These at-risk residents’ stories were often distressing and hard to hear. These people were lonely and in crisis. It was hard, but to ensure the help got where it was needed we had to keep our efforts focused on those community members facing the highest number of compounding factors. We realized that newcomers consistently faced more compounding barriers than any other group, and the culmination of these factors could create an insurmountable challenge for people who wanted to, but couldn’t, stay in Kingston. This was an opportunity to intervene early to help improve long-term prospects for newcomers.

Stacking challenges for jobseekers

Stacking challenges for jobseekers

Inclusion and immigration are important to Canada and the Kingston community. This is not only a demographic necessity but, according to Immigration Refugees and Citizenship Canada, diversity helps to build cultural vibrancy in communities. We believed, and continue to believe, that this cultural vibrancy can address employment challenges and address the primary concerns of the employment shortage in the Kingston area.

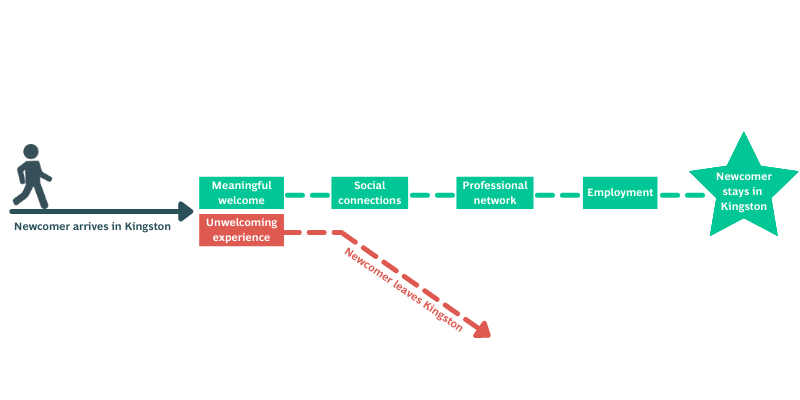

Before we could advance any further, we had to acknowledge an uncomfortable truth: the Kingston community can often exclude newcomers.

This is a problem. Whether explicit or implicit, exclusivity makes newcomers feel unwelcome and can drive them away from meaningful, stable employment in Kingston. This can derail them personally and professionally and hampers long-term workforce development and economic stability. This exclusion pushes people to leave the community and restart their lives elsewhere. Research collected through our interviews shows that the pandemic and physical distancing amplified these dynamics, and this underscores the need for a retention strategy to support long-term financial recovery.

Disparate newcomer experiences

Disparate newcomer experiences

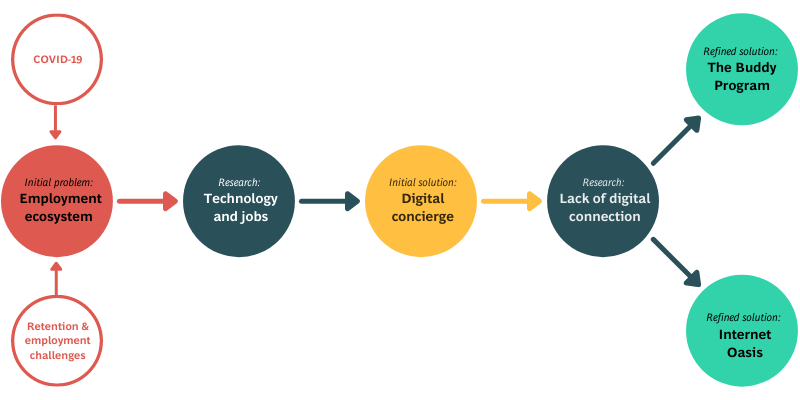

Our initial solution was to create a “digital concierge” - an online platform with which residents could engage to find necessary services. Using Artificial Intelligence, we would be able to connect residents to disparate services. At first glance, this seemed like the perfect approach. Once created, the digital concierge would be extremely efficient, cost-effective to maintain, and provide a much-needed junction for extremely valuable community resources, that don’t otherwise coordinate with each other, to overlap.

We’d like to say that the problem was resolved at this point by a technology-driven solution, but that’s not the case. In this case, technology was part of the problem.

As a team, we were frankly too excited about the new promise of a tech-driven solution and all of its future possibilities, including impacts on operating costs. But, instead of removing barriers, we created them. This was based on a troubling, but understandable, assumption: that everyone can engage digitally. This was not the case and, going back to our first round of resident interviews, our research proved it.

Coming to this realization involved a careful examination of our own biases as City staff. We had access to technology and were able to quickly adapt to remote work during the pandemic. Not only were we already employed, but every single staff member had access to an internet connection and the majority of those connections were extremely fast and reliable. Our employer also provided technology support to bridge any gaps we were experiencing.

By questioning our biases and conducting research, we identified one big problem: people need one person who can open many doors for them. Access to technology is a symptomatic issue, but not at the heart of the problem. The digital concierge would not be successful because it lacked the one-on-one element.

This pivot was a major lesson for the entire project team: we had an implicit bias because we already had the doors open for us. We passively knew this was the case, but interview-based research caused us to confront this reality because it allowed us to see through someone else’s eyes.

Umbrella programs don't work. While appealing, a one-size-fits-all portal would miss important elements that would be integral to jobseeker success. Specifically:

Language barriers are more prevalent than originally suggested. In a few instances, we needed to work through translators for some of our resident interviews.

Newcomers are often more comfortable speaking to a person, as opposed to an agency or a technical interface.

Personal and professional relationships are hard for newcomers to develop. There is value beyond employment in helping newcomers find a place in their community.

The second round of interviews with newcomers and newcomer advocates was critical. We gained a richer sense of what barriers to employment really looked like and realized that the need for a friend was a major part of this formula because it was the foundation for a community network.

This was a real and present challenge faced by community members, including City staff.

It was initially hard to settle in Kingston due to the lack of socio-cultural diversity in the community. However, getting a job at the City positively impacted my experiences and inculcated a sense of belonging by allowing me to start developing a network. - Lakshay Raheja, Innovation Analyst and Project Manager for the Kingston Innovation Training Team

We realized that Kingston had many systemic and systematic barriers for newcomers and, as staff, we had a specific role in dismantling them. While systemic barriers are often community-wide and based in procedures and processes, they are composed of systematic barriers. As local government, we have the power to dismantle systematic barriers in the hopes of addressing broader systemic challenges.

These new insights were reflected in our two news solutions:

The Buddy System: an in-person concierge service to welcome newcomers and connect them with both social and employment opportunities. This program will compensate for current gaps in existing service offerings across the Kingston community. It will also immediately solve the need for social connection, providing an interim solution while newcomers develop a community and network of their own.

The Internet Oasis: a program that offers affordable high-speed internet access, recycled technology hardware, and training. This will address the primary challenge of the digital concierge approach: access. Similar to The Buddy System, this program will bridge gaps between community program offerings. In addition, it will help to catch individuals who were falling through the cracks due to technology and capacity discrepancies between current programs.

Kingston's innovation journey

Kingston's innovation journey

Prototyping showed that these programs were viable, scalable and in-demand solutions. All that remained was implementation. This takes us to May 2021. With vaccination programs in full swing and a return to “normal” on the horizon, the community will begin to shift its sights to economic recovery.

There’s no doubt that these programs will be critical in pandemic recovery efforts by promoting sustainable economic development and community resilience, but the COVID-19 reality means that there are competing priorities.

Staff are currently working through an implementation strategy for both programs and are exploring funding supports that will help inform our deployment timelines. As a community, we’re trying to figure out when and where these programs will fit best to create the most impact among recovery efforts.

In the meantime, we can appreciate the impacts of Innovation Training on our current work. Craig Desjardins, Director of Strategy, Innovation & Partnerships for the City and Kingston Innovation Training Team member commented, “Innovation Training was an opportunity for the City of Kingston to fundamentally transform how it operates by providing new skills and approaches to help staff better understand and address the complex problems we often face. The greatest and most immediate benefit of this program has been shifting how we work as a municipal government.”

To be successful, ideas must be impactful and empowering for both staff and residents. During Innovation Training, City staff were able to step outside of the government machine to test implicit bias through the program delivery, with meaningful changes in the outcome. We learned by empathizing with residents and testing assumptions.

It was an honour to be one of only two Canadian cities selected to participate in this training program. As a city, we strive to promote innovation in our organization and in every sphere of our community. I know that this was a transformational experience for staff. I look forward to seeing them pilot some of their solutions and to seeing the skills they’ve acquired in action to further our innovation goals. These approaches will transfer beyond this program and will help distinguish Kingston as a city and a community that embraces creativity and promotes flexibility and experimentation. - Mayor Bryan Paterson

Human-centred design creates an agile framework for continuous improvement of City programs and services. We recognize that government programs are often developed in a vacuum, away from full engagement and consultation with users. Innovation Training reminds us that residents are an integral part of the policymaking process. Most importantly, this project demonstrated just how human policy interventions are. Instead of creating and delivering the answers, we’re learning to ask questions.

The challenges facing metropolitan areas - including decreasing social mobility, climate change, and pandemics - are more complex than ever.

There are no obvious answers to these problems. Addressing them will require new governance models and a combination of technological, social, and political solutions.