Human Learning Systems - A practical guide to doing public management differently

In this @CPI_foundation article, @tobyjlowe shares what we're learning from the #HumanLearningSystems Action Learning Group, leaders from across the world who are already experimenting with the approach.

Share article.@CPI_foundation's #HumanLearningSystems Action Learning Group enables people to have a sensemaking conversation about how they're applying the approach in their work. Read key reflections from the first meeting.

Share article📣 Join our #HumanLearningSystems Action Learning Group, and share how you've been applying the approach in your work with others who are exploring it too!

Share articleWe put our vision for government into practice through learning partner projects that align with our values and help reimagine government so that it works for everyone.

One of the privileges of working at the Centre for Public Impact is that we get to explore our vision for government in many different country contexts. One of the ways this has manifested is the demand from across the world to further explore putting a Human Learning Systems (HLS) approach to public management into action.

To help meet that demand, we are bringing together leaders from across the world who are already experimenting with the HLS approach (or who are ready to do so) to learn from their experiences. We are calling this group the Human Learning Systems Action Learning Group.

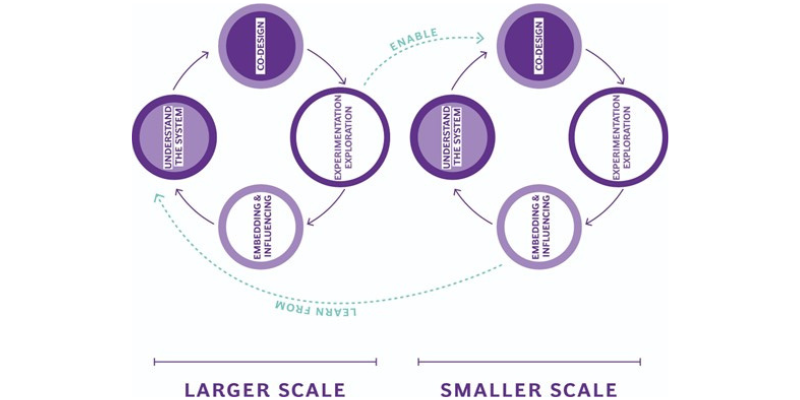

We’re exploring different ways for the group to learn together. Our initial approach has been to enable those who have been doing the work to present detailed case studies of the HLS approach in action. We have structured those case studies to highlight how they have enacted Learning as a Management Strategy, using the framework of connected Learning Cycles across different system scales. This is something we explored in depth as part of the recent HLS publication, ‘A practical guide for the curious’ (download via this form).

Our idea is that by enabling the group to have a sensemaking conversation about the detail of the work, we will be able to develop, improve and iterate our understanding of the what and how of HLS theory and practice.

The group met for the first time in July and discussed the work of the North Devon Pathology Service. The headline story is that by asking the question “what information do clinicians, and the patients they serve, need to make good healthcare decisions?” they were able to improve outcomes for patients and reduce unnecessary testing activity by 40%, saving both time and money.

Several key themes emerged from our discussion of the case study.

Whilst the entry points for HLS Learning Cycles can come from any system scale (country, place, organisation, team or practitioner), HLS learning processes are intrinsically built from the ground up. Change at higher levels comes from deep listening to, and experimenting alongside, the people being served, and the practitioners who serve them.

Senior leaders play a very important role in creating permission for and signalling the importance of, these ground up learning processes.

One of the critical advances in recent HLS thinking and practice has been the identification of connected Learning Cycles as management strategy and practice (see diagram below). The core idea is that the creation and management of these Learning Cycles become the core task of management, replacing the current focus on setting and monitoring predefined programme activity indicators. This framework seems to provide a very helpful way to understand the shape of management work.

But there is a danger in simply representing this work as a process to be followed. The group identified the crucial way in which relationships underpin learning processes. Simply put: without trust, real learning doesn’t happen. The strategy of creating connected Learning Cycles, therefore, relies on human processes of trust and relationship building. This is not an approach that can simply be mandated from on high.

People needed to be actively involved in undertaking experiments and creating knowledge, for that learning to translate into change.

An interesting reflection is that learning is often viewed as a passive activity - the absorption of knowledge or information gained from elsewhere. The learning processes which worked in this context were active processes of participatory experimentation. People needed to be actively involved in undertaking experiments and creating knowledge, for that learning to translate into change.

Interestingly, this seemed to hold across the range of system scales in this work. At the person/practitioner scale we heard a brilliant story of a patient being actively involved in their own learning process:

‘There was one patient, who had recently lost his wife, who was repeatedly going to their general practitioner (GP) complaining of heart problems. For a long time, the GP resisted ordering a cardiogram for the patient because the recognised procedure is to only order a cardiogram if there are clinical signs of heart problems - which there weren’t in this case. (And the whole purpose of this experiment was about reducing unnecessary testing!) And so the GP would repeatedly tell the patient “you’re clinically fine, you’re experiencing symptoms of grief”.

But the patient kept returning, complaining about his heart. And so eventually, the GP did an experiment within a Learning Cycle which they privately called “just do the bloody cardiogram and see what happens”. And when that cardiogram came back with an ‘all clear’ the person themselves was able to say - “you know what, I’m probably just grieving”.’

This experience - of the importance of actively involving people in experiments as ways to create change was replicated at higher system scales. When presented with data from one GP practice where GPs and nurses had experimented with creating a new set of blood tests, which seemed to produce results for less work, nurses in another practice refused to believe the results - thinking that the purpose of the newer tests was cost cutting, not patient care. It was only when they were able to do their own experiments, based on those of the other practice, that they also shifted towards using the new set of tests.

This effect was repeated at the place scale, all the way through to the national scale: it is much less effective to simply share information. If you want learning to create change, then learning must be an active process of discovery.

The group identified a very interesting virtuous relationship between learning and dissonance. In our previous work on understanding the paradigm shift in public management that a shift towards an HLS approach entails, we had identified a prior sense of dissonance as a key factor which must be present to enable this kind of radical change. You can’t talk people into a paradigm shift; they must have an internal sense that something is fundamentally wrong with the current way of thinking and doing.

Our discussion identified that dissonance is both a trigger for doing things differently, and is also nurtured by learning processes. Therefore, it is possible to cultivate dissonance through a particular type of learning. This kind of learning involves deep listening to those being served, and the forms of active experimentation described above.

What do forms of governance look like that ensure that Learning Cycles are creating the kind of positive change that they are designed for?

One of the other key areas that the group was curious about was how Learning Cycles can be governed. This frequently revolves around questions about the role of senior leadership and politicians - either at a place or national scale. What do forms of governance look like that ensure that Learning Cycles are creating the kind of positive change that they are designed for? And what do the accountability mechanisms which accompany that governance look like?

One of the interesting avenues which the group pursued as a way to begin to answer this question was through the idea of creating “alarm systems” around Learning Cycles. What kinds of behaviours would trigger a governance alarm? What would non-compliance with accepted learning practice look like? If examples of these can be created, then assurance can be offered that governance of Learning Cycles is both possible and functional.

The group also reflected on how to engage senior leaders with Learning Cycles - as currently senior leaders often have an impossible desire for certainty. The discussion in this context explored helping senior leaders to focus on what they will get from learning processes, rather than what they won't get: momentum for change, the ability to test assumptions, get insight, and make real what is currently intangible. These seemed like particularly effective tactics in situations that senior leaders already recognised as ‘wicked’ or complex problems.

This first meeting of our Human Learning Systems Action Learning Group was hugely insightful and offered a great opportunity for members to share their experiences and learn from one another. We’re hosting these sessions to support people across the world to apply the HLS approach. We’re already planning our next session in October and can’t wait to see where our next conversation takes us.

Are you currently exploring HLS approaches by enacting Learning as a Management Strategy, or ready to start doing so? We’re always looking for new members who can help us learn and broaden our perspectives.