Measurement for Learning: A Different Approach to Improvement

.@anthromarc reflects on his work in San Francisco's Human Services Agency to discuss why success metrics are a problem in public services, what causes them and what might be done differently

Share article"Staff asked us why their performance was being measured by how quick they answer calls or how many they answer. They’re unclear what matters most since we aren’t measuring if callers were helped." @anthromarc on the need for better success metrics

Share articleExperiment with incremental tweaks, understand the policy, include other insights that could serve as a comparative dataset or unpack artefacts of assessment critically. These are some of @anthromarc's practices for better success metrics

Share articleWe put our vision for government into practice through learning partner projects that align with our values and help reimagine government so that it works for everyone.

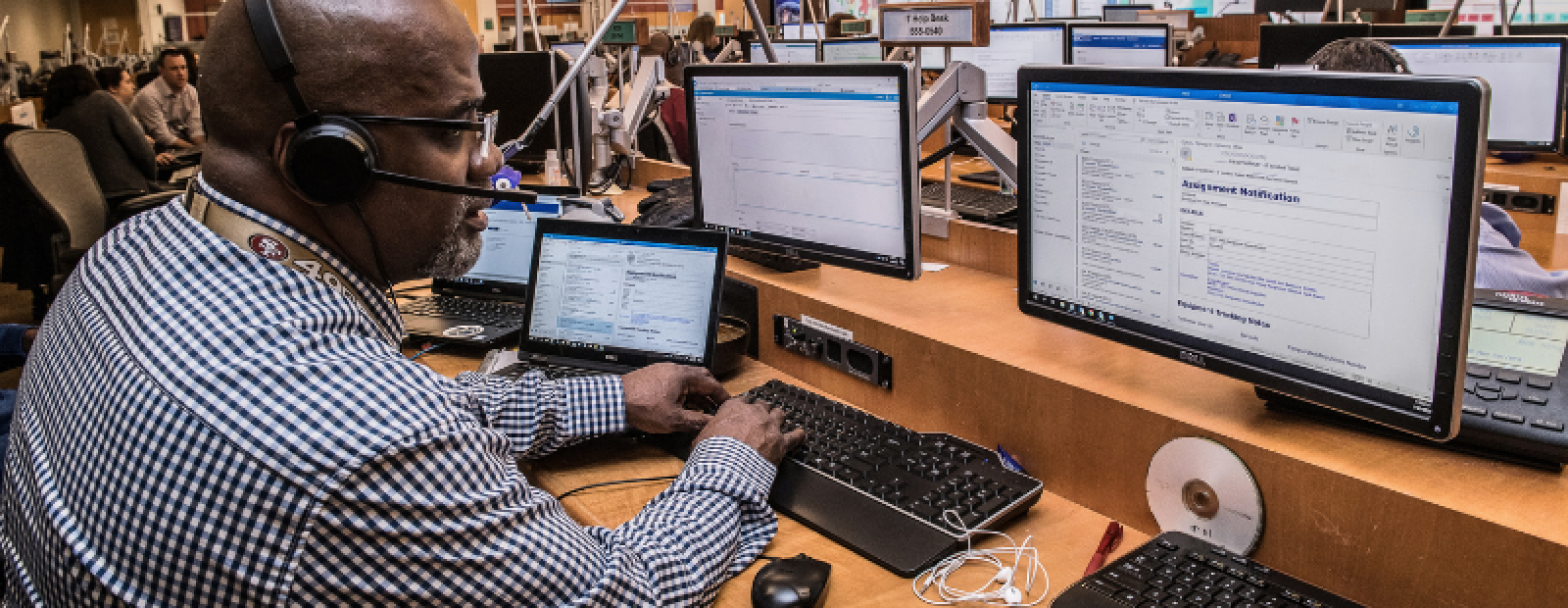

In San Francisco’s Human Services Agency, we use call centers to help the public with questions about public assistance with food, medical, and homecare services, among other critical needs. Call center teams are an important touchpoint with the community, but the way their service is assessed was called into question. As a colleague shared with me something along the lines of:

“Staff asked us why their performance was being measured by how quick they answer calls, how long people are on the call and how many calls they answer. They’re unclear what matters most to customer service since we aren’t measuring if callers were helped or how many times they have called about the same issue or were transferred to someone else. We aren’t asking callers for feedback about their experience.”

For some time, one call center team admirably made not having anyone hang up a primary goal. Reducing wait times that lead to dropped calls are an important part of helping the public. Without accompanying measures of whether people felt helped or measured their experience in any way nudged managers to focus on the data they had, rather than the data they needed. Without more complete insights, call center employees were not supported to achieve their primary purpose.

Yes, worldwide. There are even scientific laws that explain the inherent flaws in standard performance management metrics. Success metrics (key performance indicators, data dashboards, audits, evaluations, etc.) are frequently used to manage and control what we do and how we do it. As a result, we can fixate our attention on meeting the metric (e.g., # of people served) rather than its intended result (e.g., # of lives saved). Focusing on the metric instead of its intended results is aggravated by information silos where people are not collectively working towards a shared understanding of success or what matters. This is partly what gave rise to the creation of Outcome-Based Agreements, Results-Based Accountability, Objectives and Key Results, and Empowerment or Developmental Evaluation, among other frameworks.

History, discrimination, and trauma can shape success metrics, but are not considered.

Organisational values are not part of projects’ or individual employees’ success metrics.

Not co-designing success metrics nor assessing them periodically between frontline teams and managers or among diverse stakeholders to projects.

People’s judgment and stories of their experiences might be left out of success metrics.

Little knowledge about data or its use in an organisation.

Available data is more easily measurable than necessary data.

There is no genuine agreement on intended results of a product, service, policy, etc.

Spiral of Mistrust: Frontline teams feel metrics are meaningful only to managers/central government. In response, these teams treat the metrics as a checkbox in order to return to the real work. Managers/central government discover this is happening and respond by creating more metrics to control the frontline teams. The downward spiral continues.

Uncertainty of how to have these conversations or shame at what they may reveal.

Here are some practices we use on our team that may be adapted to your context. No need to follow them in a set order. Pick what works when needed.

Identify: Ask yourself or your team whether there is more pressure on meeting indicators than achieving impact? Consider showing them the Sketchplanations of Campbell’s and Goodhart’s laws as a conversation starter. Ask whether they or others experience this pressure, and why (not)?

Reflect: Set aside time to unpack artefacts of assessment critically. Adapting the language of Public Design for Equity, consider leading a conversation with these sorts of questions:

What might frontline employees and the public like to say about our data dashboards and reports that hasn’t been said?

Do our data practices move us toward relationships and understanding with others?

People experience their government through a historical context of power, privilege, discrimination and trauma. What would acknowledging this history look like on our data dashboards and performance metrics or through the ways people grow in our organisation?

What are the approaches to how our data is gathered, stored, shared, accessed and analyzed say about our equity and inclusion practices?

What assumptions need teasing out to better use success metrics for our policies, programs and individual job performance?

Include: Policy analysts, design researchers, and others in government could add questions about how people experience success metrics in their interview guides, surveys, and facilitations. They might ask what pressure people face to meet performance indicators, audits, or benchmarks. They could inquire about what is not being measured that could be or what stories about impact should be known. These insights would then serve as a comparative dataset to the existing “official” dashboards, reports, or evidence being used.

Check the policy: There are legally required metrics; however, digging into them can reveal a gap between what really is a codified mandate compared with a gray area for interpretation, a historic practice, or even individual preference for a particular metric. Understanding the policy helps to know what exactly could be changed or interpreted differently.

Test: Experiment with incremental tweaks based on the policy and evidence about how diverse groups of people experience performance, audit and evaluation targets. There are facilitation practices we use from Liberating Structures and Reinventing Work that may help. They include panarchy to guide project collaborators towards making connections between our individual actions and broader systemic forces (e.g., measurement procedures and practices). The other is consent decision-making that can assist a group to arrive at agreement.

Start a conversation with colleagues or be inspired by others doing this work or contact me for help or to share your lessons learned. There are allies in this space who freely publish their work, including the Rapid Research Evaluation and Appraisal Lab at University College, London. I partner with them as their anthropological approach to research includes data ethnography in their practice with collaborators worldwide.